“Every soldier who served on that mission received the Medal of Honor, except for two soldiers who died because of that operation, but who never received that recognition,” Biden said. “Today, we are righting that wrong.”

The event marked the culmination of a decades-long campaign by the men’s families to correct what they and many historians saw as an unwarranted omission in recognizing all those involved in what would become known as the Great Locomotive Chase.

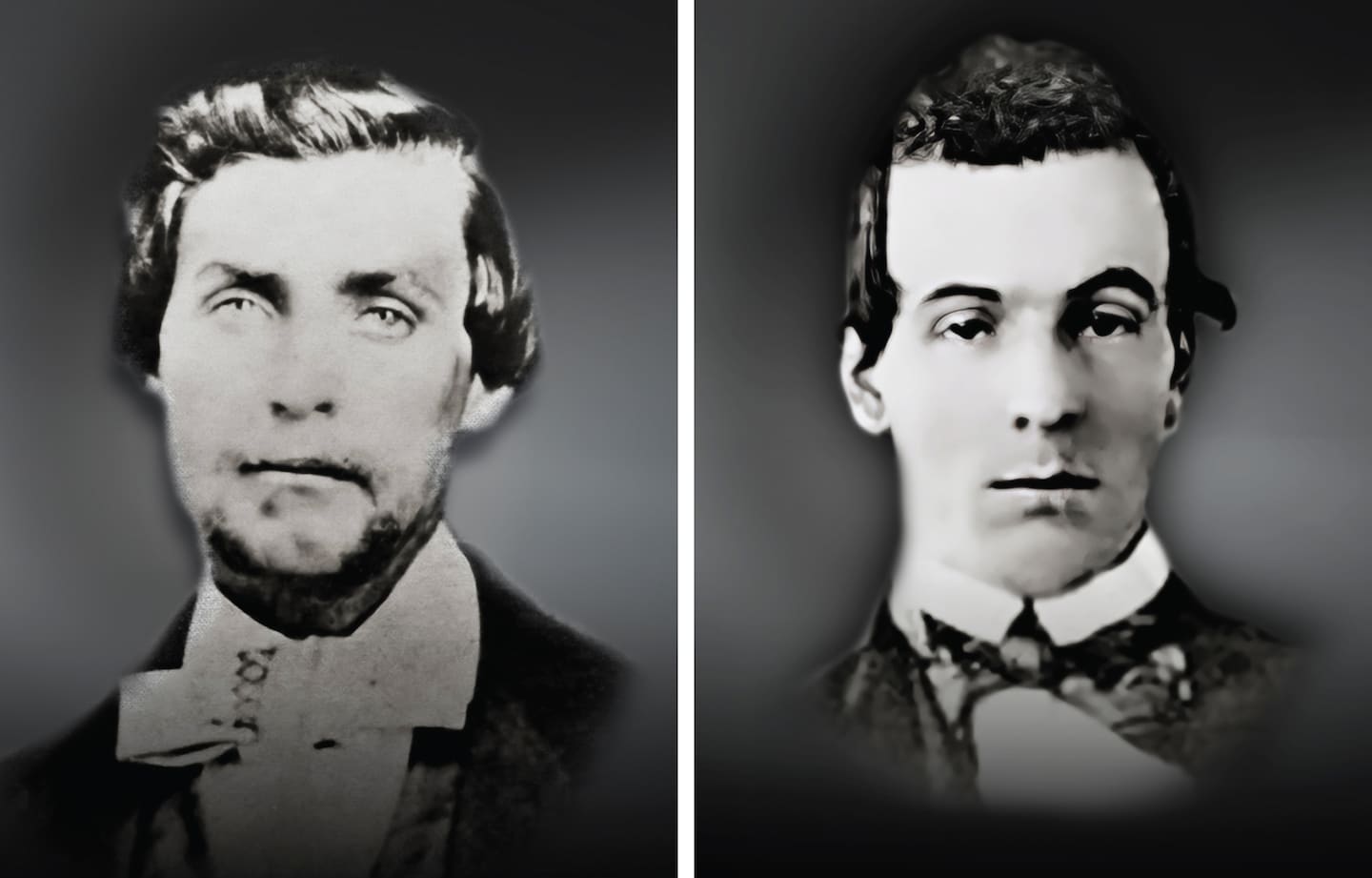

Shadrach and Wilson were among a group of 24 who carried out the audacious plan in April 1862, seizing a train outside Atlanta and blazing an 87-mile trail of destruction north through Georgia to the Tennessee border, with opponents in hot pursuit. When the chase finally ended, the raiders were captured and eight were put to death. Most escaped, although several were held as prisoners of war for nearly a year.

Nineteen soldiers received the Medal of Honor—including the first ever—for their roles in the mission. (Several were recognized posthumously.) Another soldier, captured before the raid began, later refused the award, historians say. Two others involved were civilians and didn’t appreciate it.

During an emotional conversation with reporters on Tuesday, the descendants of Shadrach and Wilson expressed great pride, knowing that the efforts of their ancestors and the advocacy of their families, along with historians, would finally be recognized.

Some who made the trip to Washington had known the story for a long time. Others, including Wilson’s great-great-granddaughter Theresa Chandler, only learned from the Army four years ago that her lineage included a prominent Civil War figure.

Now 85, she says it has changed a legacy that was almost lost to history.

“I would have given anything,” she said, “to be able to say, ‘Grandpa, tell me about it. … What was it like?’”

The mission arose from a desire to destroy the South’s ability to move troops and military equipment.

Major General Ormsby M. Mitchel, assigned by the Union to the Tennessee campaign, considered how best to attack Chattanooga, a well-defended Confederate citadel located along important water and rail lines. If attacked directly, the Rebels could flood the area with reinforcements on rail cars from the south and overwhelm the American forces, he concluded.

James J. Andrews, a civilian spy for the North, came up with a novel solution. A small team of volunteers would travel 200 miles into Confederate territory dressed as civilians, steal a locomotive, and then destroy tracks and burn bridges to strangle the secessionist logistical lines.

The plan had setbacks from the start, said Shane Makowicki, a historian with the U.S. Army Center of Military History. It had rained before the mission, making it difficult to burn the bridges. The soldiers had no tools and had to improvise, he said. And while some had experience with trains, little to no preparation had been made.

“That speaks volumes to the courage and heroism of these men that they volunteered to do this,” Makowicki said. “If we were to send people out to do this today, you would need months or weeks of specialized training.”

The mission, led by Andrews, began north of Atlanta in present-day Kennesaw, Ga., where the team seized a locomotive named the General and its three freight cars. The conductor, William Fuller, gathered a posse and gave chase on foot before commandeering a handcar and eventually several other locomotives to catch up with the Union soldiers.

The raiding party stopped frequently to pull out sleepers and cut telegraph wires to prevent other Confederate troops from learning of the raid. Oncoming trains on the single track forced the general to stop several times, according to an Army summary of the mission.

In other cases, the raiders used guile to get past the authorities. At one stop, Andrews told a station master that he had been ordered by General P. G. T. Beauregard to deliver ammunition to Confederate troops in Chattanooga. The station master let them pass.

As Fuller and his group closed in, Union marauders aboard the General, short on wood to fuel the locomotive, abandoned it 18 miles short of Chattanooga, the Army said. The men scattered, but were eventually all captured within two weeks.

Chattanooga fell the following year.

Andrews and seven others, including Shadrach, 21, and Wilson, 32, were tried as spies and saboteurs and hanged. Jacob Parrott, who was severely beaten in captivity, was one of those who survived the ordeal and later made history as the first service member to receive the Medal of Honor.

Historians and family members could only speculate why Shadrach and Wilson were overlooked for so long. The unit had been involved in heavy fighting afterward, and officers who would have kept up such feats were sent to other units, said Brad Quinlin, a historian and author who has been involved in advocating for the Medals of Honor for men.

Some members of the Shadrach family had been pushing for the recognition since the Carter administration, they said. A 2008 budget bill included a provision to award the medal to the two men, but momentum didn’t pick up until 2012, when Quinlin and family member Ron Shadrach met in person. They later submitted new evidence for defense officials to review.

“There was nowhere in my research, in any documentation, that indicated that these men did not do what the others did,” Quinlin said.

Although the mission ultimately failed, it is remembered as a key moment of the Civil War and has spawned books and films, including Buster Keaton’s “The General” in 1926 and “The Great Locomotive Chase” in 1956.

Brian Taylor, Shadrach’s great-great-great-nephew, said he was impressed by the family history dive, and that doing it with his father deepened their relationship. They affectionately call Shadrach “Uncle Stealer,” and Taylor once climbed aboard the General, now a museum piece in Georgia.

For the White House ceremony, Taylor strummed an acoustic guitar and sang a song he had written about the mission. “Do it for the glory, boys,” he sang, “‘Cause you might not find your way home tonight.”